On every single trip out on the Holly Jo, looking for wildlife at sea, there is one marine mammal you are guaranteed to encounter– the Atlantic grey seal, and like all marine mammals, they have evolved to become sophisticated and successful creatures in the cooler waters of the north east Atlantic. They are protected from the cold by a thick layer of blubber, just as whales and dolphins are.

Almost every offshore rock and uninhabited island off the Irish coast, is a place where seals can be seen, both in the water, and ashore on the rocks, resting or sleeping through the hours of daylight. They are seldom seen hauled out on the mainland, or any place accessible to humans or dogs, and with good reason. They were killed and eaten by humanity over thousands of years, and are wary of humans to this day, when out of the water. But almost the opposite is the case when they are in the water, and often approach people swimming, and will go as far as gently nibbling at the flippers worn by snorkel and scuba divers, out of sheer curiosity.

In the clear waters around Ireland, seals tend to do a lot of their feeding at night, under the cover of darkness, when it is much easier for them to approach and hunt down fish, using the super-sensitive whiskers that sprout from either side of their noses, and their huge, light-sensitive eyes. These whiskers can detect the very slightest of disturbances in water, even the tiny wake of a fish that moved through the water a few minutes before. If the seawater is heavily clouded by sediments, they become far more diurnal in their foraging for fish. It is rare to see any seal looking thin, emaciated, or poorly; they are obviously quite adept at finding enough to eat, and appear to live very healthy contented lives. The females live to the age of 35 or so, while the males expire at 20 to 25 years, from the exhaustion of fighting with other males in maintaining their harem.

In the past 2 years a disturbing discovery was published, where a grey seal was seen killing and partially eating a harbour porpoise of the north coast of France, this was followed soon after, by another report in the North Sea, where a grey seal was seen to attack and kill another porpoise and then eat a large portion of it. Grey seals were always thought to prey on nothing but fish, cephlapoda (squid, octopus, cuttlefish) and crustaceans, so these reports suggest that grey seals are developing new hunting skills, directed at new prey, perhaps in answer to a lack of fish to prey upon.

Grey seals are most certainly intelligent, highly adaptable and more than capable of developing new hunting skills to suit any opportunity. I have witnessed this ability to adapt to new situations over the past 40 years, watching their activities in the waters’ of West Cork. A good example of this is the four seals that loiter around Union Hall pier, and hoover up all fish and fish discard from the fishing fleet at the pier. I’m fairly sure they do little or no hunting for live prey at sea any more. They get more than enough to eat by hanging around the pier, scavenging from the boats. Two of them, both females, have been there for 20 years or more, and all four look wonderfully fat from their chosen lifestyle.

In the water of West Cork during the early 1970’s, and before that, grey seals took no notice of fishing gear. But then, as we went into the 70’s, drift netting for salmon became a very lucrative and popular fishery, such that, by the middle of the decade, every trawler, potting boat and punt was engaged at drift netting for salmon. There were suddenly drift nets everywhere, all around the Irish coastline, from the shoreline out, with salmon securely caught in them.

Grey seals love salmon and rarely catch such a fast and agile fish, but then, one by one, they noticed the sea was full of nets with salmon stuck in them, just waiting to be taken and eaten, and took full advantage of this situation. By the 80’s it was rare to do a days drifting for salmon, without having a seal or two taking fish from the nets all day, and they do seem to have an insatiable appetite.

In the interest of conservation, commercial drift netting for salmon was banned in 2006, but to this day, anywhere there are gill nets fishing on the seabed, there is always a raiding seal in attendance, inshore or offshore, and they seem to have an uncanny skill at finding gill or tangle nets, anywhere they are placed. If there is very little fish in the nets, they will wrench the whole fish from the gear and take it to the surface, where they tear it apart and consume it in chunks. But when there is plenty of fish in a net, they change their feeding style completely. They dive down to the nets and rip open the belly of the fish, and neatly remove the liver, leaving the rest of the fish uneaten, and work their way along the nets eating as much liver as they can on each dive, leaving a trail of damaged, unsaleable fish behind them. Fish liver is undoubtedly a favourite food of grey seals and they would raid our nets in water as deep as 140 metres (as I bear witness to) in pursuit of this delicacy.

There is another skill that grey seals have developed over the last 25 years or so, linked to their net raiding abilities and their passion for liver. They have taken to hunting at shipwrecks. Where in years gone by, you would never encounter a seal at a wreck, they now make regular forages to them, off the south coast of Ireland. Even wrecks that are 60 or 70 miles offshore are regularly attended by hunting seals. This behaviour I first witnessed at the start of the 90’s, and there is a very good reason for why they hunt at wrecks, when they took no interest in time gone by……they are taking fish from gill nets that have been lost there.

There are hundreds of wrecks off the south coast of Ireland. Nearly all of them were sunk by German torpedoes or mines, during the First World War. In the next few years all of them will be 100 years on the seabed, quietly rusting and rotting away. Any of these ships in less than 50 metres of water are smashed and torn asunder long ago by heavy weather, but many of them out in deeper water are remarkably intact.

A shipwreck is a much favoured habitat for some species of fish, most notably for pollack, coalfish, ling, cod and conger eels, and huge numbers of these species congregate around and inside a wreck. It is a place where these predators can ambush forage species such as herring, mackerel, sprats and sandeels, as they are swept by in the running tide, and a place to escape their own predators, notably sharks, seals and trawler nets.

Any trawl snagged on a wreck is seriously damaged, or more often, lost entirely, such that all trawlers keep well away from them, as do potting or dredging vessels. Whilst most fishermen avoided them like the plague, I was the opposite and put a lot of time into locating wrecks, with an interest in both angling and diving on them. Over my 42 years at sea here, engaged at angling, diving and commercial fishing, I spent an inordinate amount of time at wrecks, and this provided the opportunity to watch closely the activity of seals at these sites.

In the early 80’s the technique of wreck netting was developed by Danish fisherman working in the North Sea, and huge catches of cod, pollack and coalfish were taken. This fishing technique was rapidly taken up by British and Irish boats, and I was one of the first Irish vessels to go “wrecking”, commencing in the mid 80’s, and we too made huge catches of fish in doing so. After a few “golden” years at this fishery, more and more boats went at it, until every wreck was hounded by nets, as they are right up to the current day.

The art of wreck-netting is to place 2-300 metres of mono-filament gill nets right across a wreck, securely anchored at each end, and haul them after 12 to 24 hours of fishing time. Inevitably, delicate gear like gill nets would from time to time get snagged and lost on the rotting metals down below. This lost netting goes on fishing for some time afterwards, until it is either shredded by predators taking fish trapped in it, or becomes totally covered in soft corals, anemones and more and collapses to the bottom under the weight of all the attached growth. It is this lost gear, still catching fish, that is the big attraction bringing grey seals to hunt at wrecks, for an easily caught meal.

To do anything around wrecks you need pinpoint- accurate navigation such as the GPS system provides. Pre GPS at the start of the 90’s, the only option was to use the British Decca or French Loran navigation system. Both were a land based, radio wave counting system that would give a position to about 50 metres accuracy, but was unreliable at times, especially around dawn and dusk, and it would sometimes take a long search to locate a wreck that we had visited many times before.

Grey seals have no such problems with their navigation and appear to have their own built-in GPS system and more. As the seals moved in onto wrecks, I began to marvel at their navigational skills. How do they locate the wrecks, and having found one, how do they slide effortlessly into position, directly above one, take a series of deep breaths and dive faultlessly down to their chosen target, in the deep and often murky and dark water below?

From pondering over these questions for a long time and watching their technique, I am now absolutely certain of the fact that seals are acutely sensitive to the earth’s magnetic field, both in polarity and intensity, and use this sensitivity for everyday navigation and, as the perfect tool to locate and guide them onto wrecks. I have some very strong evidence that this is how they operate.

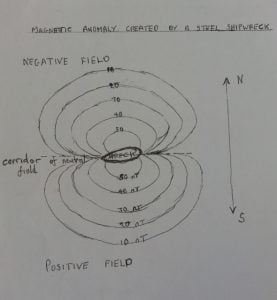

Every shipwreck made of iron or steel creates a slight disturbance in the earth’s magnetic field, usually referred to as a magnetic anomaly. We are able to measure this anomaly with the use of a magnetometer, a very clever and sensitive piece of electronics, that detects the slight change in field intensity in the vicinity of a large piece of ferric material, like a shipwreck, or areas rich in iron ore. I used one extensively for finding wrecks, with great success, and combined with the accuracy of differential GPS, came to understand the nature and extent of magnetic anomalies.

To the north of a wreck is an area of negative value, and to the south a slightly larger area of positive value. These areas are separated by a very narrow “corridor” of neutral field. Magnetic intensity is measured in nano-tesla,( nT) named after the remarkable genius that was Nikola Tesla. The term nano means a thousand millionth, so nano-tesla are tiny measurements of magnetic intensity.

This is a simplified diagram showing the nature of a magnetic anomaly created by a wreck…..

When a seal arrives at a wreck site to carry out a dive, every time the same, it positions itself directly above the wreck by sensing the very narrow corridor of neutral field that occurs between the positive and negative field, (shown as dotted line in the diagram), takes a series of deep breaths, and dives to the target below. Surprisingly, their last action is to exhale. They do not need the buoyancy of two lungs full of air to hamper their diving effort, and in deep water, with very little air in their lungs, lessens the absorption of nitrogen into their blood; a major problem for humans when diving into deep water, leading to the dangerous condition known as the “bends”, which can cripple or even kill a human diver.

The only explanation of how seals can carry out this activity, is that they are acutely sensitive to the earth’s magnetic field, and thus, the tiny changes in that field in the vicinity of an iron wreck. They must have the equivalent of a magnetometer built into their heads to be able to seek out both the wreck and then the very narrow corridor of neutral field in a wreck’s anomaly, in the way that they do. Almost certainly, they must have some kind of ferric material in their head to accomplish this.

As a little more evidence towards this, I know the location of just three wooden wrecks that do not have enough iron present to make a detectable anomaly. I have yet to see a seal at any of these sites.

This sense of field may well be how they find their way in everyday navigation. If seals are able to detect such tiny changes in magnetic intensity, they might well use this skill to ascertain their location at sea.

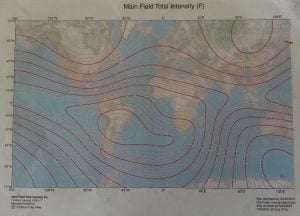

We are all taught at school how the earth has a strong magnetic field with a north and south pole. Less well known is the fact that this field varies considerably, depending on where you are on the planet. In central South America the field is low at 25,000 nano-tesla, while in polar areas it goes as high as 65000 nT. Here is a map of field intensity, published in 2010, developed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, ( NOOA ). The isobars are showing intensity at 1000 nT intervals.

On a voyage from Dublin to Land’s End, Cornwall, which is a little over 200 miles, on a north to south track, the field changes quite rapidly by 1000 nT, from 49000 nT in Dublin, to 48000 nT at Land’s End or 5 nT per mile. A magnetometer reading would give a fairly accurate idea of your position on such a journey. Whilst if you set sail from Galway, and head for Charleston, South Carolina, your field value would change very little, if at all. Using a magnetometer as a navigational instrument, together with this map, it would be possible to accurately pursue such a course, port to port. If you have a built in sense of this field, as I suspect grey seals have, it would certainly help greatly with navigation.

Finally, it came to my attention just recently that scientists from the Texas A & M University, engaged in a 20 year study of Weddel seals, arrived at a similar conclusion. They have been studying how Weddel seals find their breathing holes in the ice sheet. Tiny air holes, few and far between, that are essential for their survival. They must have pin-point navigation to find the next place to breath, and the team have come to the same idea, that the seals know the magnetic signature of each hole, by sensing the magnetic field in the same way as our grey seals can find wrecks in West Cork.

The University of North Carolina has carried out a study of turtle migration, and turtles too seem to demonstrate being sensitive to magnetic intensity. It is likely that all manner of creatures use this same skill to find their way about the planet. In the meantime we’ll have to make do with our Garmin and smartphones.

Colin Barnes

Cork Whale Watch

4 comments

stuttgartdaily.com

My family members every time say that I am wasting my time here at net, but I know I

am getting familiarity every day by reading thes

pleasant posts.

Marks Gotfredsen &

Very nice post. I certainly love this site. Keep it up!

Pádraig Whooley

Thanks for your feedback Marks

Graham

Nice article Colin.

Comments are closed.