As our August 2017 came to a close, cetacean activity was at very low levels in West Cork’s coastal waters. Somewhat surprising after a fantastic spring and early summer season, with hundreds of common dolphins, dozens of minke whales, humpbacks approaching double figures, and the occasional fin whale or two. The August/September period has always been a busy part of the year for whales and dolphins in years gone by. So what’s gone wrong?

The reason there is so little animal life currently inshore is entirely down to the fact that the sea is a green algal soup at present, offering very poor visibility underwater. This is a result of too much nutrient being present in the sea….The nutrient problem.

What has always made the seas around Ireland rich in marine life, is a healthy supply of nutrients. Upwelling deep ocean currents at the continental shelf edge, off the west coast of Ireland provide a steady supply of nutrient rich water that feeds the production of phytoplankton, which is the starting point of the ocean’s food chain. More nutrient is added by the churning of seabed sediments and seaweeds in periods of stormy weather through the winter months, and more again in run- off from the land. In great abundance, plankton is referred to as a” bloom”.

Plankton blooms occur naturally and are a vital part of the ocean’s ecology. In springtime, with ever increasing daylight for photosynthesis, and warmth returning after the chill of winter, phytoplankton is triggered into life and consumes all these nutrients. With masses of phytoplankton about, which is tiny plant life, there is then an explosion of zoo plankton, tiny animal life, that feeds on all this plant life, and the ocean food chain is started. Forage fish species like herring, mackerel, sprats, sandeels, sardines all prosper on a rich diet of all this plankton, and they in turn are consumed by most other fish species, marine mammals and oceanic birds, and humans. That is the ocean’s food chain.

The norm is that the nutrients are largely used up by high summer, and then the plankton dies off, leaving clear blue seawater. This rather critical part of the cycle is not happening the last decade or so, because of the excessive amount of nutrients in Irish coastal waters. Thick green algal blooms, clouding the seawater, persist for much of the year nowadays.

Poor visibility in seawater has a profound effect on the activities of fish, pinnipeds, cetaceans and our sea birds, by preventing the forage fish upon which they feed, forming into proper shoals. The simple fact is that the fish are unable to see each other in cloudy green water, in order to stay together in shoals, as is their survival strategy of safety in numbers. These conditions lead to thousands of tiny shoals of pelagic fish scattered over large areas with no decent sized shoals for cetaceans to prey upon. Furthermore, the fish, unable to see predators circling around them, cannot be herded into larger “bait balls”, which is how they are normally caught by both birds and cetaceans alike. Oceanic birds like gannets, shearwaters, kittiwakes, guillemots, razorbills and puffins feed by sighting their prey, so thick green algal blooms are bad news for them too.

It is no mystery why there is so much algal growth at sea; it’s created when there is too much nutrient in the water. It’s the direct result of wet weather, washing nutrients from the land in huge amounts, into our seas. The nutrients that cause most of this problem are a toxic mix of slurry from livestock and agricultural chemical fertilisers. Slurry is put out as a liquid, and in our increasingly wet climate, it is inevitably picked up by rainwater and washed into every drain, brook, stream and river; by the miracle of gravity it is promptly delivered it into the sea. Water soluble chemical fertilisers, much the same.

In modest amounts it has been seen to have an enhancing effect in seawater, by triggering rich plankton blooms, but in excess it causes far more harm than good. Over nutrification in seawater can lead to the formation of red algal blooms, some of which are harmful and toxic. Areas of de-oxygenated water can occur, with dangerously low oxygen levels, causing huge fish- kills and wiping out life on the seabed at the same time. These nutrients are now produced in vast amounts in Ireland by modern farming methods. Current EU agricultural directives suggest that slurry should only be spread in dry weather, but when there is no dry spell to do so, and slurry tanks filled to their limits, it has to become a compromise and is all too often put out, by necessity, in broken spells of weather. Other directives require that slurry be injected into the soil, a measure which should eradicate much of the problem, but thus far, there is not much sign of this being put into practice.

The scale of this kind of pollution has become a serious threat to both our inland and coastal waters. I am amazed that up to now, no-one in government seems to have the slightest concern about this situation. From my own observations made over 45 years in West Cork, the one outstanding fact about this mix of nitrates, phosphates and slurry, is that it’s a super-food for the growth of algae in both fresh and salt water.

I had the good fortune to see West Cork waters at the start of the seventies, when I moved here from the UK. I came here with the intention of making a living from fishing. I brought with me a passion for the study of aquatic life that I developed as a small boy. That passion has stayed with me my entire life. When I arrived here, all waters were pristine and heaving in all forms of aquatic life. Almost every lake in West Cork had a healthy population of trout, with salmonids and eels in nearly every river and stream, with clear water year round, and alive with insects and crustacea.

Agriculture at this time caused very little water pollution. Hay was made then, not silage. Manure was put out as a solid, not liquid, and not a drop of slurry about. Much of that aquatic life is now gone, smothered out of existence by algae, resulting from the ever increasing tide of fertilisers and slurry being spread on the land. It has now become a rare sight to see hay being harvested anywhere in Ireland. The industry of feeding livestock has almost entirely turned to silage making, which makes sense given Irish climate trends. It was always a challenge to cut good hay, and then get enough fine weather to cure and dry it thoroughly before storage. Silage making is far less weather sensitive and thus leads to more successful fodder production.

A staggering amount of silage is cut and stored in Ireland each summer, to be fed to an equally staggering number of cows through the winter months. The grass that is cut to produce it, is grown with extensive use of chemical fertilisers. Naturally then, all this activity leads to a colossal output of slurry, and in a wet climate the majority of it ends up in water. In fresh water, even when very diluted, this solution of fertilisers and slurry is taken up quickly by most species of algae, promoting their rapid growth. In lakes, riverbeds and streams, this algal growth carpets the bottom and chokes up the living space for insect larvae, tiny crustacea and all the native micro wildlife.

Salmon, trout and eels have decreased steadily in numbers in Irish rivers over the last few decades, in spite of conservation measures. This decline began when silage making, slatted cow sheds and slurry tankers became the new face of Irish agriculture in the 1970s. It is this lack of insect larvae, freshwater shrimps and all micro life in fresh water that creates this problem. A tiny elver that has made its way into fresh water needs an immediate supply of such food, as do newly hatched trout and salmon larvae. When there is little or no food they fizzle out quickly. Some fish survive by becoming cannibalistic, preying upon any larval fish smaller than themselves, and thus perpetuate their species. This is not a healthy situation.

Likewise in seawater, and seaweeds being algae, now grow vigorously in harbours and estuaries where excessive amounts of such nutrients are present, but in growing so quickly, weeds are softer, less fibrous and break up more easily in rough weather. After a summer storm, inshore waters are all too often choked with shredded weeds, that get washed ashore, often forming into drifts, to rot away odorously at the high water mark.

Recently I looked at rock pools I explored regularly with my daughters when they were children, which then harboured shannies, Montagu’s gobies, hermit and shore crabs and many more delights. They are now choked with weed growth to such a degree, that no fish or crustacea could survive in them. If as fishermen, fish farmers or boat owners, you have equipment resting in salt water, you could hardly miss all the algal growth and slime that now clings to ropes and any other structure not covered in anti-fouling paint. This slime has become more and more prevalent with time, in the ever increasing tide of slurry, particularly over the last decade or so. This too is strong evidence of over-nutrification.

With all the recent media and political noise surrounding Irish water, I am astonished that this issue has only now surfaced in the wake of this months Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) report on the poor state of water around the country. It is a massive environmental problem that won’t go away without radical action.

There is a perfect solution that would dramatically reduce this pollution. Slurry could be eminently suitable material for turning into bio fuels. If all the universities in Ireland were thrown the challenge of creating bio fuels from slurry, I’m quite sure it would not take long to produce a result. Based on the sheer volume of it, such activity would make a contribution to Ireland’s fuel demands and lessen our dependence on fossil fuels, thus lowering our carbon footprint.

In the USA there is a lot of interest and research into the production of bio-fuels from algae on a commercial scale. There are installations already making fuels from algae, notably diesel oil, and even algae farms built to produce raw material for the job. Already in existence is a brewing yeast that creates diesel instead of alcohol. A yeast or organism that broke down slurry into diesel would be the ideal process. It would be wonderful to see every farm that produced slurry, creating bio-fuels from it, instead of spraying the stuff all over the pastures. This would produce enough fuel to power the whole farm and create a commercial surplus to sell, thus providing a useful income from the farm waste. This process would dramatically reduce the carbon footprint of Irish agriculture, currently driven almost entirely by fossil fuels.

Until such time as Irish farmers and their lobbyists accept their role in the health of our rivers and seas, we can but dream of Irish rivers running with clear, algae free water and teeming with life, and a summer sea that looks blue, not green.

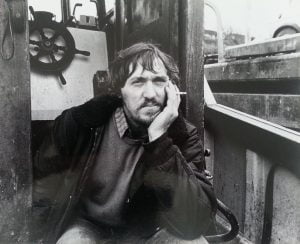

By Colin Barnes

Cork Whale Watch